EthnicityThe term Nubia is widely used by scholars and the media to refer to the ancient civilization of Kush. Although some still identify Nubia with the ancient Egyptian word nub for gold, scholars are increasingly casting doubt on this assumption. Evaluation of scattered evidence suggest that Nubia and Kush were historically two different socio-cultural entities. While Kush is the actual name of the ancient Nile Valley civilization of Sudan, the term Nubia has probably evolved as an alternative pronounciation for the Noubades, or Nubians, a pastoral people who occupied Sudan's Nile Valley starting from the second or third century CE and overpowered the Kushite kingdom in the sixth century. Hence, the Kushites and the Nubians may have represented two seperate and distinct ethnic populations.1

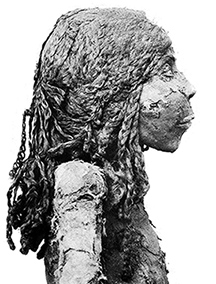

While the Nubians continue to form a distinct ethnic minority in Sudan (15%), there is no longer a recognized Kushite ethnic identity. The domination of the Nubians in the third century, followed by the spread of the Arab identity in conjuncture with Islam in the fourteenth century, has probably contibuted to the extinction of the Kushite ethnicity. Instead, the vast majority of Sudanese today identify with Arabic lineages (70%). These lineages include the Jaa'lyeen, Shaygiya, and Manasir. The biggest difference between the Nubian and Arab populations is language. While the Nubians traditionally speak dialects of the so-called Nubian language, the Semitic population speak Arabic. Genetic research2 and linguistics indicate that the modern Nubians are indiginous of North Sudan. The contemporary Nubian language is calssified by the majority of linguists as an Eastern Sudanic language. The latter constitutes a branch of the Nilo-Saharan language family spoken by native populations of the Middle Nile and adjacent regions in the Sahara. Since the Nubian identity is still existent, one may assume that more Kushites and less Nubians have embrassed the Arabic identity. In this context, the Semitic population may be viewed as more Kushite in ancestry than the Nubian. However, this is not to deny the probable presence of Kushite ancestry within the Nubian population. The fact that they evidently originate from virtually the same gene pool, indicates that no significant intermixture with outsiders has taken place. Whether Nubian or Arabic in identity, the people of North Sudan are mostly indistinguishable in physical characteristics. We have a good idea of how the ancient people of Kush—or ancient Nubia— looked like for they have depicted themselves in numerous wall reliefs, painting sculptures, and as confirmed by the anthropological studies of fossils. Accordingly, it is certain that they physically resembled the modern day riverine people of Sudan.3The Arab identity is therefore more language and culture based than genetic. The origins of the North Sudanese populations may be traced back to prehistory. It is widely suggested that the material culture of the human population that emigrated out of Africa during the Middle Paleolithic, had originated in Sudan.4 Many of the earliest human tool industries and techniques originated in Sudan including the Nubian Levallois technique for producing pointed flakes, bifacial foliates, and pedunculates.5

|