|

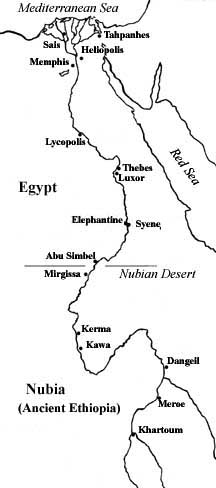

Elephantine is an island in the Nile River, to the west of Aswan (on the eastern bank of the Nile). In ancient times, the island has been the southern-most city of Egypt. South of Elephantine, for a distance of approximately 223 km, extends the Nubian Desert where even the Nile banks are inhospitable. Beyond this distance lie the lands of Sudan, homeland of the Nubian civilization, which to ancient Egypt represented a prominent military threat. Trade relations between Egypt and Nubia continued active throughout history and Elephantine was the point where trade routes from Nubia met. Hence, to the ancient Egyptians, the city represented the 'door to the South'.

The name Elephantine is Greek meaning 'elephant' and this expresses the city's function as a gate to the South, since elephants were brought from the south towards Nubia. Another name for the city by ancient Egyptians is 'Yebo', which also meant 'elephant'. A Jewish garrison community that was already settled in the island by the fifth century B.C., played an essential role in the interaction between Nubia and Egypt. Some historians and archeologists directed attention and research towards this Jewish community for it provides a wide range of evidence for the earliest Diaspora Jewish settlement. The task of the Jewish garrison in Elephantine was to protect the Egyptian border with Nubia (Kush). However, the garrison was also associated with insuring the safe passage of products coming from/to Nubia. Adjacent to the Jewish settlement in Elephantine was the Aramean garrison at Syene (Aswan), on the eastern bank of the Nile. While less evidence was available for the Armaean garrison at Syene, extensive records documented life within the Jewish garrison at Elephantine. In Elephantine the Jews built a temple for 'Yahweh', which resembled the Salomon's temple in Jerusalem. During the fifth century B.C., contemporary with the Persian rule of Egypt, the temple was destroyed by Egyptian rebels and at which time the Jewish settlement mysteriously vanished. A collection of archives (known as the Elephantine Papyri) mostly written in Aramaic, and some in Hieratic and Demotic is found. The archives are concerned with diverse matters of the community; i.e. political, legal, social, economic, and religious. Some documents that belonged to members of the Aramean garrison were also found at Syene. The collection of the archives has been first discovered and purchased by Giovanni Belzoni from a local market in Aswan (Egypt). A.H. Sayce and A.E. Cowley published the first collection of the papyri in 1906. Later excavations revealed more Papyri and ostraca. Thereafter, more publications followed such as those by W. Staerk and A. Ungnad. Most of the archives associated with the Elephantine Jewish community date back to the Persian period, i.e. after 525 B.C. Owners of the contracts secured their documents by burying them under the floors of their houses and keeping them inside pottery vessels and jars. The Legal documents found are concerned with lawsuits; sales; marriage, loan, gifts, and other contracts related to property ownerships. The judicial court to which these contracts were drawn in accordance is uncertain (i.e., Persian or local Jewish courts). Although most of the contracts were written in Aramaic, they seem to have followed the same formula as that of the Egyptian contracts. It is proven for certain, nonetheless, that members of this community were Jews. There names, identity, lifestyle, and religious traditions leave no doubt for their Jewishness. There is proof that they had observed the Shabbat and the Passover, and probably most of the other traditional Jewish holidays. Of special importance is the 'Passover Letter' which dated back to 419 B.C. The letter was from Hananiah to Jedenaiah of the Jewish garrison at Elephantine. On his letter, Hennania instructed the Jews to "keep the Festival of Unleavened Bread" and to "be pure and take heed."(C:21:6) along with other instructions related to the observance of the festival. Scholars suspect that this Hennaniah might have been the brother of the legendary Biblical figure, Nehemiah. However, the Jews were not living in total isolation from their pagan environment, which, beside the Arameans, included Greeks, Babylonians, and Egyptians. Cases of intermarriages are documented and names bearing both Pagan and Jewish elements existed. Family archives, on the other hand, provided a wide range of information with regard to the social structure that this Jewish community had enjoyed. p Members of the garrison owned Egyptian slaves and took handmaidens regularly. Although the living standards at Elephantine are not well known, the Jewish settlers were certainly wealthier than the average Egyptian commoners. Some of them seemed to be real state, owning several houses; many kept more than one Egyptian slave and purchased expensive gifts for their brides -- 10 Shekels on average. One of the most illustrative documents in the Elephantine Archives is the marriage contract of Ananiah b. Azariah, who was a treasury keeper of the Temple, to the Egyptian slave girl Tamut. Although Tamut was the wife of Ananiah after the contract was drawn, she still belonged to her original owner Meshullam b. Zaccur. The Letter of AristeasThere are only two documents that relate to dating the settlement of the Jewish garrison at Elephantine. The first one is the Letter of Aristeas, which scholars believe to have been written in the second century B.C. The letter documents the Greek translation of the Pentateuch in Alexandria. Also documented are historic events and circumstances that relate to the emigrations of Jews into Egypt. It is mentioned on a certain part of the letter that Jews "had been sent to Egypt to help it's king Psammetichus in his campaign against the king of the Ethiopians (Nubians)."(The Letter Of Aristeas: 13). Note: 'Ethiopia' in ancient literature referred to Nubia in modern Sudan, not modern Ethiopia. Since the Egyptian king Psammetichus II is known to have carried campaigns into Nubia, it's most likely that the Letter of Aristeas meant Psammetichusis II, not Psammetichus I. ' The second document was written by the Elephantine Jews on 410 B.C., which claims that when "Cambyses came into Egypt he found this Temple [Jewish Temple at elephantine] built."(C 30: 13f). Most scholars support the suggestion that the Jews settled in Elephantine during the reign of Psammetichusis I. Out of three succeeding Judean kings, contemporary with Psammetichusis I, Manasseh is thought most likely to have been the Judean king who dispatched the Jewish troops that settled at Elephantine. It must be noted that Psammetichusis I was the first Egyptian ruler after the periods of Assyrian and Nubian rule. Psammetichusis I and the Nubian king Taharqa were allies at a time when Assyria represented a common enemy. After Assyira was expelled from Egypt, Psammetichusis I was cautious to secure his position on the thrown of Egypt. His most dangerous threat were certainly his former allies, the Nubians. Contemprary with this Egyptian king it was recorded Egyptian soldiers from Elephantine left Egypt and departed to Nubia for a better life. Psammetichusis I would have needed troops to fill in the positions of the Egyptian soldiers who departed. Hence, Manasseh may have aided the Egyptian king by sending him soldiers. Information related to the campaign of Psammetichusis II campaign into Nubia is found inscribed on the colossi of Ramses II at Abu Simbel. As indicated on the inscription, the Nubian campaign of the Egyptian pharaoh started from Elephantine. The Pharaoh's military was composed of Egyptian as well as foreign troops. The later included Phonecians, Carians, Ionians, and Rhodianss. In southwest Asia, Judea had been paying tribute to Babylonia. During the reign of king Jehoiakim, Judea rebelled from the Babylonian superiority and stopped paying the tribute. Soon, Nebuchadnezzar the king of Babylon, who was recently crowned after the death of his father Nebopolassar, marched to reinsure his rule on the Levant. When the Babylonian king reached Jerusalem he found king Jehoiachin, son of the deceased king Jehoiakim, on the thrown of Judah. Jehoiakim surrendered to Nebuchadnezzar in 597 BC. On his place, Nebuchadnezzar appointed Zedekiah whose original name was Mattianiah. However, Zedekiah also rebelled. Contemporary with this period, the Biblical prophet Jeremiah warned the people of Judah that rebelling against the Babylonian supremacy would lead the Jews into captivity. He also warned against migration to foreign lands and doomed the Jews of foreign lands for abandoning the Holy Land. However, the warnings of Jeremiah went unheeded. During these events, on 591 BC, Psammetichusis II carried his Nubian campaign. If indeed Jewish mercenaries were sent to Egypt during the reign of Psammetichusis II, then King Zedekiah would have been responsible for the act. This is because king Zedekiah was the only ruler of Judah contemporary with Psammetichusis II. Since, Egypt would have been most likely to support anti-Babylonian rebels, the presence of Jewish mercenaries in Egypt might have been viewed as an act cooperation against a common enemy. Examining other ancient sourcesOn 589 B.C. Apries succeeded Psammetichusis II as the king of Egypt. Contemporary, Nebuchadnezzar marched with his troops to put down the rebels in Judeah. Soon, the Babylonian troops captured and devastated the Holy City. On August 587 BC the Holly temple of Solomon, was destroyed and the first Diaspora of the Jewish people has begun. Thousands of Jews were exiled to Babylon leaving Jerusalem desolate. Apries was well known for supporting the anti-Babylonian movements in the Levant. He supported king Zedekiah on his anti Babylonian policy. However, when the Babylonians attacked Jerusalem, the Egyptian king did not intervene. Escaping the Babylonian captivity, thousands of Jews from Judea flooded into Egypt. Thus, is written in the Bible in regard to Jewish migration to Egypt: "At this, all the people [remainder of Jews in Judah] from the least to the greatest, together with the army officers, fled to Egypt for fear of the Babylonians."(2 Kings 25:26). During the reign of Apries there was a large garrison of foreigners stationed at Elephantine who also sought to depart from Egypt and seek refuge into Nubia. Neshor, the governor of Elephantine, was able to convince the mercenaries to cancel their plan. Among these foreign mercenaries, 'Asiatics' are mentioned. Perhaps the term 'Asiatics' referred to Jews and/ or Arameans. Still later, an inscription dating to the reign of Amasis mentions an expedition into Nubia that included 'Palestinians' and 'Syrians'. During the last years of king Apries reign; civil wars in Egypt divided the country into North and South. The rebels from Upper Egypt were objecting to the policies of king Apries, which favored the foreigner troops over the Egyptian. These rebels crowned Amasis as king of Egypt. On the other hand, the foreign troops from Lower Egypt fought for king Apries, only to be defeated. Hence, Amasis became the king of Egypt. The question would remain; If Jewish mercenaries had indeed settled at Elephantine during the reign of Apreis, what role did they play in the civil war? Egypt has always been a source of refuge for the people of Judea starting from the Great Biblical Patriarch of the Bible, Abraham. After the Diaspora, Jews flooded into Egypt and established the largest Jewish communities there; perhaps, since the time of Moses. During the Persian period they were Jewish garrisons posted at Tahpanhes and Migdol. During the sixth century B.C., 'First Isaiah' prophesized return of the Jews "from Assyria, from Lower Egypt, from Upper Egypt, from Kush [Nubia], from Elam, from Babylonia, from Hamath and from the islands of the sea."Isaiah 11:11) As indicated in the passage, Isaiah probably knew about Jews residing in Nubia at the time. 'Deutero-Isaiah' (second Isaiah), who supposedly lived during the exile in the fourth century B.C., prophesized the restoration of Israel. On one passage he mentions the return of Jews from the region of Aswan as follows: "See, they will come from afar, Note the statement, "some from the region of Aswan." clearly indicates that the prophet was well aware of Jewish presence in the region of Aswan or Syene. In any case Elephantine is and was certainly not excluded from the region of Syene. The presence of a Jewish garrison at Elephantine clearly does not predate the period of Assyrian conquest of the sixth century B.C. The archeological evidence and the documents discovered for this Jewish community at Elephantine suggests a time of settlement that is, by far, not prior to the Assyrian conquest. It was also after the Assyrian expansion that the use of foreign-paid-mercenaries became wide-use in the Near East. The story of Onias IV might hint the origin of the Elephantine Jewish communityEvidence for the Jewish temple at Elephantine comes from the local archives of the settlement. As quoted before, it is mentioned that the Jews of Elephantine in the third century B.C. wrote that when "Cambyses came into Egypt he found this Temple [Jewish Temple at Elephantine] built."(C 30: 13f). The Jews of this community regarded their temple as no less holier than the temple of Solomon in Jerusalem, and their settlement as no less blessed than the land of Israel. For example, reference was made in one of the archives to "Yahweh the God who dwells in the fortress of Elephantine."-K 12:2. Holocausts, meal offering, and most of the other traditional sacrificial ceremonies performed at the Temple of Solomon were performed at the temple of Elephantine alike. The site of the temple at Elephantine has not been located yet; however, geometric calculations based on houses that are known to have neighbored the temple, indicate that the dimensions of the temple resembled that of the Solomon Temple in Jerusalem. Also descriptions of the temple as known from the archives prove the later as true.

As known, Jewish religion prohibits the building of temples outside of Israel; rather, the building of Synagogues is sanctioned. This law stems from the Jewish devotion to the land of Israel; that the sacredness and holiness of it's soil is unmatched anywhere else on earth. Hence, in accordance to the Jewish laws and traditions, erecting a Temple on foreign soil; such as that of Elephantine, should have been considered unlawful and contradictory to the Jewish cause. The only other Jewish temple that was indeed built to resemble the temple of Solomon was the Temple of Onias IV. This Onias belonged to prominent family in Jerusalem and his fathers held positions of priesthood in the temple of Solomon. He lived during the first half of the century B.C., when Judea was ruled controlled by the Maccabees. Onias expected to be appointed as High Priest, however Judas Maccabees refused to place him on the position. Since Onias IV was also a friend to the king of Egypt (Ptolemy Philometor), he built his own temple at Leontopolis (modern Tell-el-Yahudya) on the eastern Delta, few kilometers north of Heliopolis. He justified that the Maccabees have unpurified the Jerusalem Temple and that his temple was the only sanctioned one. Since Onias was popular among the Jews, he was accompanied to Egypt by a large number of followers. His followers later constituted a large garrison near Memphis. Their settlement was known as the "Country of Onias" Is it possible that Onias IV was merely following an example of an earlier Jewish leader who might have established the Jewish community at Elephantine? Fate of the Elephantine Jewish CommunityDuring the reign of Darius II Egyptian rebels threatened the security of Upper Egypt. First, The Jews of Elephantine sent a letter to some Persian official in which they complained against the Egyptian priests of the temple of Khnub and some other military personnel named Vidranga for committing some acts of destruction in their fortress and for burying a well where the Jews were used to drink. The other document dealt with the final destruction of the temple in 410 B.C. According to the document, the Egyptian priests of Khnub cooperated with Vidranga who sent his son Nefayan in command of an Egyptian army and ordered "the temple of the God Yahweh in the Fortress of Elephantine to be destroyed"(C 30: 4ff) The Jews of Elephantine greatly lamented the destruction of their temple, just as the Jews did when the temple of Solomon at Jerusalem was destroyed more than a century before. They wore sackcloth, went into fasting, refrained from sexual intercourse, stopped anointing themselves with oil, and prohibited themselves from drinking wine. The reason for the Egyptian violence towards the Jews is probably social as well as religious. For centuries the Egyptians were suppressed under foreigner rule. People from other lands, including Judea, have emigrated and settled in Egypt occupying prestigious positions. The Egyptians felt that they were being downplayed, not only by their direct conquerors, but also by other foreigners. Religious reasons too might have encouraged the Egyptians to take action against the Jews. Elephantine was known as land of the god Khnub. Originally Nubian, this god is represented as a ram-headed man. The sacrifices of the Jews on religious holidays at the temple, which probably included rams, would have caused hatred on part of the Egyptian priests. Soon, the Persians interfered and captured and punished the Egyptian rebels; however, not much attention was paid to the Jews. The Jewish leaders of the community pleaded and begged before the authority of Jerusalem to interfere on their behalf by requesting from the Persians to rebuild their temple at Elephantine. When their letters went unanswered, they begged for a response.

Then they turned to the Persian satrap for support, and promised to stop the offering of Holocausts, which included sacrificing sheep, oxes, and goats, if their temple was rebuilt. As mentioned the sacrificing of rams in the temple was clearly a major cause in the rebelling of the Egyptians. Yet, there is no evidence to indicate that the temple was rebuilt sometime later. Although, many of the houses belonging to Jews adjacent to the temple show signs of reconstruction, the situation at the time remains mysterious. The last letter was dated to 399 B.C., which was written to Islah. Unfortunately, the content of the letter is unclear. The unknown fate of the Jewish community at Elephantine can be variously interpreted. One possibility is that they may have immigrated to Nubia, just like the Egyptian soldiers did during the time of Psammetichus. The tragic encounter of the Jews with the natives of Elephantine or elsewhere is not the only one in history of the Jewish nation; however, the absence of reference to the Jews of this community in the ancient sources is particularly odd. The fact that the Jews of Elephantine were devoted the land of their settlement, almost, the same way the other Jews were devoted to Israel, is particularly unique in the history of the Jewish nation. The attempt of the Jews of this community to recreate an artificial environment of Jerusalem in their settlement doomed failure. I think the fact that the Jewish members of this community did not return to live at Elephantine may return to their conviction that there is no land for which they can build and occupy with pride and confidence, but their own land. Farther readings:

On the contemporary Jewish community of Sudan see The Jewish Magaine: The Ottoman Jewish Community of Sudan. |