HistoryThe Expansion of Kerma: A-Group and C-GroupArcheological evidence indicates that by the mid-fourth millennia BC the cultural affluence of the Dongola Reach has expanded to other regions and societies across the Nile Valley. Kerma, within the Dongola Reach, became the headqurters of political leadership and the center of economic prosperity in the Middle Nile. The expansion of the culture of the Dongola Reach, and that of Kerma in particular, is best attested in the well studied A-Group and C-Group societies of Lower Nubia.

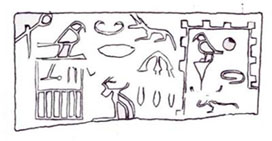

While the Dongola Reach had a relatively high population density, Lower Nubia was comparatively low in population. Being predominatly arid and difficult to cultivate, Lower Nubia may be best described as a buffer zone between Sudan and Egypt. Due to their ethnic and cultural affiliation with Sudan, the people of Lower Nubia have represented a threat to the national solidatary of ancient Egypt, particularly in the Predynastic period. The Egyptian Pharaoh Menes, considered by many scholars to be the first true king of Egypt, considered defeating the Kushites as a necessary step to unifying Egypt. The ancient Egyptians referred to Sudan as Kash, or Kush--of which Kerma was the primary municipality-- or alternatively as Nehasay.1 They also called Sudan Ta Sety meaning "land of the bow";2 that is because the Kushites were popular in the ancient world for their efficiency in using bows. One of the oldest Egyptian depictions of a Kushite person is found in an inscription from Gebel Sheikh Suleiman in Lower Nubia, in the Sudan's nothern border.3 The inscription is dated to Predynastic Egypt and shows a scorpion and a bound Kushite captive. The Kushite identity of the captive is defined by his feather. Another figure, in the same inscription, is shown with a bow, which is a symbol of Kush. Beside indicating the importance of Sudan in the development of Predynastic Egypt, the inscription suggests that the people of Kush were active in the affairs of Upper Egypt. Such conclusion corroborates the infiltration of the Kerma culture in Lower Nubia as attested in the archeology of the A-Group and C-Group. The A-Group: The A-Group population flourished in Lower Nubia around 3500 BC. The tumilus burial tradition, along with other visual evidence extracted from pottery analysis, indicates that the Group has originated from the Dongola Reach area of Sudan. The Sudanese origin of the Group has been supported by recent research,4 which dismissed the traditional theory that claimed native Lower Nubian roots.

The A-Group population practiced flood plain agriculture, animal husbandry, and conducted trade.5 Unfortunately, the Group's settlements cannot be traced in precision because of two reasons. First, their houses were built of perishable materials, such as unbaked-mud. Second, the Group's settlements were established very close to the Nile river where seasonal floods would have destroyed them long time ago.6 Therefore, most of what we know about the A-Group culture comes from the cemeteries located few miles away from the Nile Valley. The material culture uncovered from the burials suggests a complex culture with a hierarchical structure.7 Excavations in cemeteries, in Sudan's northern border area, provided a good insight on the social complexity of the Group.8 The sizes of the graves there indicate the social status of the deceased. The larger the grave the richer was the deceased, and the smaller the poorer was the deceased. Excavation in A-Group cemeteries, uncovered everyday life tools. Findings included jewelry, weapons, plates, beakers, storage jars, and cups. Pottery, however, is the most abundant of all the grave finds, and has been essential for informing archeologists on the culture of the Group. Incised and impressionistic decorations are typical of the A-Group pottery and attest to the Sudanese roots of the culture. Foreign pottery from Syro-Palestine and Egypt has been found in considerable amounts indicating that the Group has practiced extensive trade.9

An important A-Group cemetery is located in the modern village of Qustul.10 Some graves there reach 34.34 square meters.11 Their roofs were built of Timber and were found containing high quality goods including gold and copper objects.12 Owners of these graves were leaders of some sort; however, whether they ruled all of Lower Nubia, or parts of it, is unknown. An incense burner was found depicting the figure of a pharaoh, who was probably Kushite according to the type of fashion he was depicted as wearing. (The dress included a long belt that dangled all the way down to the knees, i.e. a typical Kushite dress).13 The archeological evidence for the economic and social structure of the A-Group indicates a chiefdom, or perhaps a princedom. Recent analysis have pointed to the elite burial tradition of the silo-pit among the A-Group, which originated from Kerma.15 The fact that A-Group's pits were much smaller than those of Kerma, may indicate a vassal-kingdom relationship. In other words, the A-Group chiefdom is likely to have been a subordinate to the more powerful kingdom of Kush, centered at Kerma. Accordingly, the rulers of the Group may have not been more than princes or vassals to the kings at Kerma. This suggestion would explain the disappearance of the A-Group when Egypt took control of Lower Nubia in 2900 BC. As suggested by some scholars, it appears more than likely, that the Egyptians have expelled the A-Group.16 No archeological evidence indicates the continuation of the A-Group after 2900 BC, (except for little traces of the culture in the second cataract area). It appears more likely to scholars that they were expelled by the Egyptians and probably forced to return to their ancestral homeland in Sudan. The C-Group: The C-Group settlements were excavated in Sudan dating to as early as 2300 BC. Like the A-Group, the C-Group have also originated from the Dongola Reach area of Sudan.17 The C-Group culture has essentially evolved from the older and more expanded Kerma culture. Both, the C-Group pottery and the Kerma pottery were usually polish in red and brown colors. However, the C-Group pottery is characterized by more complex designs that cover most of the pot's surface. The Kerma pottery is characterized by little designs; however, with carefully painted bands of colors around the opening. Like the A-Group, the C-Group were organized into chiefdoms. Since 2600 BC, the kingdom of Kush, of which Kerma was the capital city, has been actively pushing its northern frontiers into Lower Nubia. The direct connection between the C-Group and Kush may not have only been ethnic and cultural, but political as well. Like the A-Group, it is highly possible that the chiefs of the C-Group were vassals to the Kushite state. This observation is attested in the evidence that suggests that the Egyptian have viewed the C-Group as enemies, or foreign intruders. After 2000 BC, the C-Group area was heavily guarded by the Egyptian military.19 The Egyptians colonists built fortresses to control the C-Group and deprived them of their weapons. Dating to the last phases of the C-Group in Lower Nubia, which lasted until 1550 BC, burials were done in Egyptian-like graves. Thus, it is likely that the C-Group have melded with the Egyptian populations. There, they assimilated to the Egyptian culture, thus contributing to the mixed social and cultural structure of Lower Nubia.20

Edited: Feb. 2009. |