BurialsThe Pyramids of SudanDue to the lack of archeological work in Sudan, only few Kushite pyramids have actually been dated and explored. The oldest known Kushite pyramid is dated back to the eighth century BC. This pyramid, located at el-Kurru, is identified as belonging to Pharaoh Piankhy (747-716 BC).1 Although numerous pyramids are found at el-Kurru, Nuri, Jebel Barkal, and Meroe, many pyramids have withered away and are no longer identifiable. Thus, the exact number of pyramids in Sudan cannot be known. Currently, the identified ones number more than 230, more than double the total number of Egyptian pyramids (i.e. 81 pyramids), though smaller in sizes. Unlike in ancient Egypt, pyramid building in Kush was not restricted to members of the royal family. The priests and high-ranking officials of Kush commonly had small pyramid structures placed on top of their graves, which is a distinguished aspect of Kush’s funerary archeology.

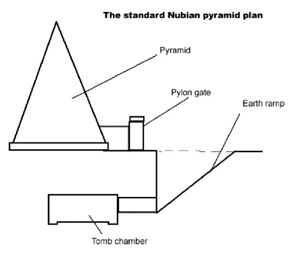

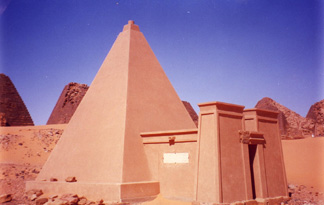

The Kushites continued to build mastaba and tumulus superstructures until the fourth century AD; a practice that have been nearly abandoned by the Egyptians since the second millennia BC. Some authors considered this as evidence to the hypothesis that regards the Kushite civilization to be ancestral to that of Egypt. The Kushites built pyramids in a wide variety of angles and styles. Kushite pyramids are distinguished by their steep angles; between 65° and 77°.2 Their average height is 13.5 m and average base area is 25.5 m2. A small peak of gold is thought to have been placed atop several pyramids, none of which escaped the hands of thieves. Most of the grandiose pyramids are built of solid masonry; many were plastered and painted white. Unlike the Egyptian pyramids, which had their tomb-chambers cut within their pyramid structures, the tomb chamber of the Kushite pyramids were dug under the ground, below the pyramid structures.

The walls of most of the tomb chambers, such as that of King Tanwetamani, were lavishly painted with religious motifs describing the judgment ceremonies of the deceased in the afterlife. Bodies of the deceased were typically mummified and their organs were placed in canopic jars. Mummies were placed on extended positions in wooden coffins or on top of beds. Religious texts inserted within the mummy’s wrap provide us with a valuable source of knowledge on Kushite religion. Objects such as shabits and canopic jars offer valuable evidence on burial practices and traditions. The tomb chambers of Kushite pyramids contained some of the ancient world’s finest treasures. Such treasures included seals, jewelry, furniture, weaponry, horse riding implements, as well as personal ornament materials such as kohl and perfume pots.3 Pottery and ceramics, some of which are rated by archeologists among the ancient world’s finest types, were found in tomb chambers in extensive amounts. The Meroetic era tomb chambers also included large quantities of precious materials, some of which seem to have been imported from around the Mediterranean world. One tomb, contained silk from Central Asia, and another contained an amphora from Roman-Algeria.4 Until further excavations are conducted, our knowledge of these great ancient monuments will remain lacking. Currently, theft is an ongoing problem that threatens the preservation of the treasures hidden within the pyramid sites. With minimum support from the Sudanese government, a number of international preservation organizations and academic institutions are struggling to maintain and insure the security of the country’s valuable historical sites that form an essential part of the global human heritage.

|