BurialsNapatan-Meroitic BurialsAfter the Kushite rule in Sudan began to blossom again, in about the mid-eleventh century BC,1 local cultures expanded and developed in complexity. The Napatan-Meroitic era is about a thousand and three hundred years. Unfortunately it would be impossible to cover all the complexities and dynamics of burial practices for such an expanded period of time in such a short article. Therefore, the purpose of this article is to provide a general and a basic outlook on the burial traditions practiced by the Kushites through the period as concluded from a wide range of archeological excavations and historical records.

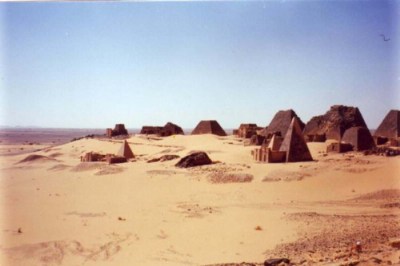

During the Naptan-Meroitic period, the Kushite population grew and expanded demographically along the stretch of the Nile Valley, from Wadi-Halfa in the north to el-Gezeera region south of Khartoum.2 The major cemeteries are located in the big cities, i.e. el-Kurru, Napata, Sanam, and Meroe. Elaborate royal burials for the period were uncovered at el-Kurru. One of the earliest dated royal burials for the period belongs to, probably, a king (i.e. with an unknown name- labeled ‘Lord-A’), whose reign is thought to have begun in about 890 BC.3 Many known burial traditions from the Kerma period continued into the Napatan-Meroitic period. These include bed burials within tumuli (i.e., often associated with royal burials) and the tradition of placing the deceased on bed.4 On later periods more variations in burial traditions came into the scene. The most popular form of royal burials for the rulers at el-Kurru were coffins.5 The basic structure of the coffin is usually consisted of wood and, often, inlayed with gold, ivory, as well as other materials for decorations. On the other hand, coffins are frequently found in non-royal cemeteries. Sarcophagus burials (associated with pyramid superstructures) were excavated dating primarily to the Meroitic period.6 Sarcophagi were usually made of stone.7 Rich people sometimes built themselves small pyramids or simply roofed their tombs with stone blocks, sometimes resembling mastabas.8

Cemeteries of the commoners varied greatly in sizes and findings, depending on the status of the deceased. The practice of mummification persisted in the Napatan-Meroitic period and was not by any means limited to the royal class.9 Yet, the majority of the locals were buried in simple pits. The deceased were placed on different body orientations depending on the location and date of the burial ground. For example, while in Kerma the bodies were usually facing north, in el-Kurru the deceased were normally laid in an east-west orientation.10 Side-niche pits were made only to accommodate the body on its side. On other cases the body was placed on its back. Also, cases in which the bodies were placed on crouched positions are also abundant. Various conclusions may be drawn regarding the deceased body orientation at the period. Excavations suggest that orientation was usually towards the east as the case with the el-Kurru royal burials, which supports the popular religious theme of rebirth as connected to the direction of sun rise.11 The case differs with other cemeteries, where bodies were found buried with diverse orientations. Hence, there was no single manner of burial. Grave FindingsAccording to Kushite beliefs, the dead should be accompanied in the afterlife by what they possessed in their lifetimes. Accordingly the deceased were buried along with their important lifetime possessions. As a result, archeologists discovered treasures and diverse daily life materials in graves, which enabled us to gain inavaluable indications on the culture and life in ancient Nubia. The excavated royal graves, including pyramid tomb chambers, contained some of the ancient world’s finest treasures. The treasures included seals, furniture, weapons, horse riding implements such as trappings, jewelry, and personal ornament materials such as kohl and perfume pots.12

Pottery and ceramics, some of which were rated as some of the ancient world's finest types, on the other hand, were found in large numbers. Tomb chambers from the Meroitic era also included large quantities of imported materials from around the Mediterranean world. One tomb, contained silk from Central Asia, and another contained an amphora from Roman-Algeria.13 Of special concern are findings that improve our knowledge of the Kushite religious beliefs. Wall inscriptions and illustrations are an important source of information on religion. The walls of the tomb chamber of king Tanwetamani's mother (Qalhata) provide details about some basic religious beliefs. They were painted with motifs that describe the judgment of the deceased in the after life.14 Religious texts usually inserted within the mummy’s wrap also help improve our knowledge of Kushite religion. Objects such as shabits and canopic jars, shed light on the ritual practices. Jars and containers were discovered in large numbers. On the other hand, burials of lower classes contained everyday life materials with different qualities depending on the status of the deceased. Accompanying pottery and ceramics were personal ornaments such as kohl, jewelry, and figurines of gods and goddesses.

Animal sacrifice seem to have continued in Kushite traditions. In a royal grave at el-Kurru, twenty-four horses were found sacrificed in connection with the sun deity represented by a falcon and a sun disk. Human sacrifice, though uncommon, has continued. Many rich graves contained carelessly slaughtered persons who seemed to have been servants.15 Almost every grave with a superstructure contained a funerary chapel. There, fragments of broken pottery were often found. This ritual of breaking pottery after a funerary ceremony has taken place is a burial tradition that goes back to the Kerma period.16 This ritual is not limited to graves with chapels. The quality of the pottery represented the economic status of the deceased. On rich graves, shreds of fine pottery were discovered, while in poorer graves the quality of the pottery is much less.17 Animal sacrifices in front of yards of the graves or tomb chambers were regularly performed.

Edited: Jan. 2009. |