Art HistoryRemarks on Palace ArchitecturesAncient constructions that seem to be palaces at their time are discovered throughout Northern Sudan. Yet, due to the lack of archeological study in the area, it is difficult to speak of them in depth. So far, archeologists have excavated and identified a few dwellings that date back to the pre-Kerma period (4th millennium BC- 2600 BC)1. The planning of the major Pre-Kerma settlement, in the locality of the Eastern Kerma Cemetery, reveals an urban architectural system, where monumental buildings, rectangular storage houses, cattle pens, palisades, and storehouses were uncovered. Exceptionally large huts, with one reaching 7 meters in diameter, found there have been interpreted by some as residence of wealthy individuals.2

Moreover, a large number of buildings were found within the expanded town of Kerma. Due to the lack and the inconsistent nature of Nubian studies, however, the original function of much of the Kerma discovered buildings is not yet possible to know. Several buildings have been identified as royal residences; usually consisting of interconnected rooms and courtyard enclosures.3

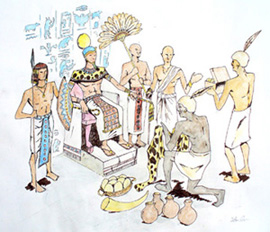

A fancy building at Jebel Barkal expanded with palatial apartments4, thought to have been built by Piankhy, was identified as a palace. The building has undergone continuous modifications throughout the course of history making its actual function difficult to configure within the overall urban structure.5 The architectural materials, structures, and the presence of staircases in most of the palaces suggest that they were mostly built of more than one floor. The majority of them had rectangular or square plans with long corridors and narrow rectangular rooms; a hallway was usually present after passing through the main entrance. An interesting building-plan at Wad Banaga was identified as a palace. The structure was built with baked bricks and doors were made of stones. Many of the entrances had stone columns and Hellenistic designs. The walls of the palace were plastered and some sections (of the walls) were adorned with gold- leaves.6 The names of Amanikhable7 and Amanishekhato (10-1 BC) were found written on a cartouche in the palace. At the Great Enclosure at Musawwarat es Sufra, three structures identified as temples were built within wide porches that were connected to each other through narrow entrances. Two temples are connected to a set of rooms identified as "throne rooms" that are thought to have been constructed as royal residence. A long corridor connected to one of the temples, leads to an elevated 'Window of Appearance'.8 The window is opened to the widest porch in the complex, where perhaps ceremonies were performed.

|